Roots

Street art in the form of text and simple graphics made in public locations supposedly originated during World War II. “Kilroy was here” is often considered the first viral inscription created by a certain Kilroy, who worked at a bomb factory in Detroit, USA. Initially, the phrase was being placed on the boxes with bombs produced there. Later, it was complemented with a simple line-drawing of a long-nosed man and further being distributed by American soldiers.

The practice began to flourish in the 1960s in the city of Philadelphia, USA that is still considered the historic center of graffiti culture. In the 1970s, it made its way to New York, starting in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan. At that point, tagging appeared. Then came the tradition of having a street number next to a nickname. The writers began a strong rivalry to be recognized as the best, which provoked a rapid and uncontrolled growth of the movement. And as time progressed, a shift occurred from text-based works to visually conceptual street art.

The first street art museum was founded in St. Petersburg, Russia in 2012 on the territory of a still operating Laminated Plastics Factory.

Forms of expression

Any visual art with a pronounced urban nature could be classified as street art. By the beginning of the 21st century, it has developed into complex interdisciplinary forms. Graffiti, stencils, prints, stickers, mosaics, reverse graffiti, installations, video projections, or even performances — the possibilities for street art media are endless. New approaches are emerging all the time as artists struggle to find their unique style and stand out from the crowd.

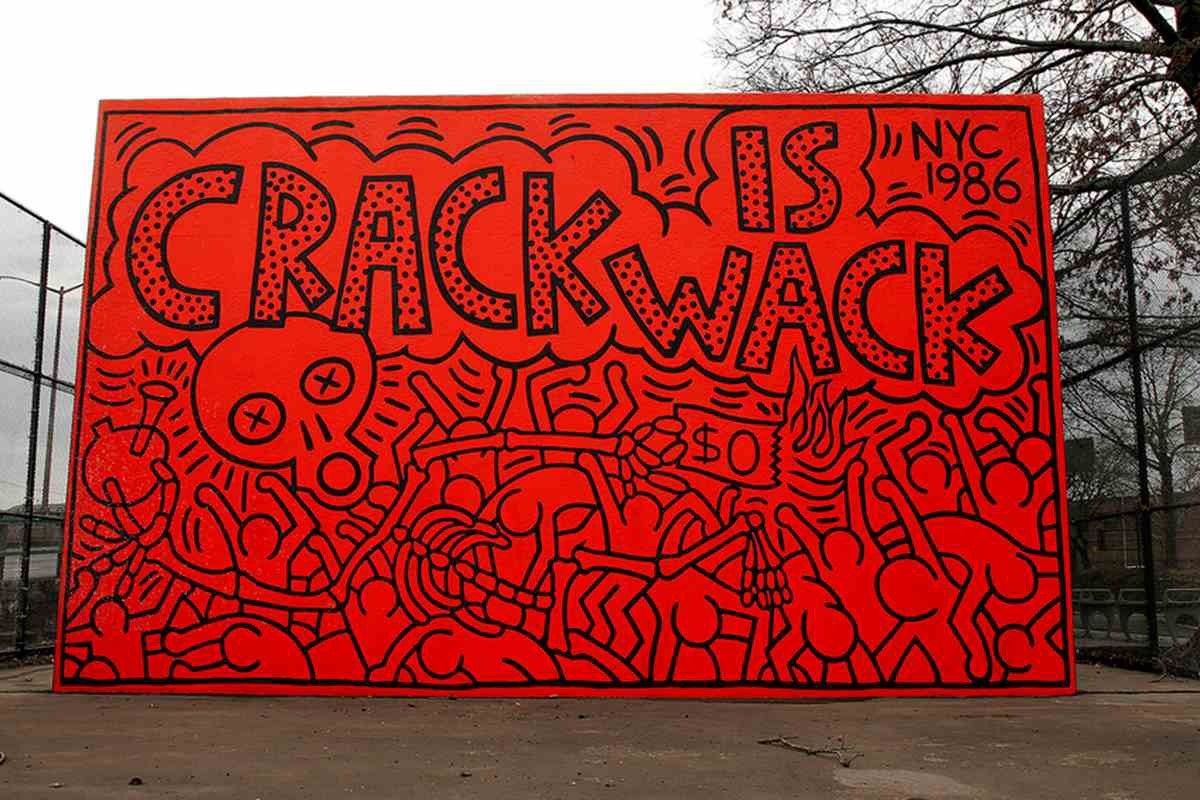

Graffiti

The term includes all forms of inscriptions on public surfaces. Most often, it’s associated with highly stylized and abstract lettering and/or cartoon-like characters and involves bold color choices.

Stencils

They are usually made in advance from paper or cardboard, then taped to the surface and spray painted over, resulting in the image or text being left behind once they are removed.

Posters

Posters are handmade or printed graphics on thin paper that are pasted on to surfaces or hung vertically. Much like stencils, they are preferable for street artists as it allows them to do most of the preparation beforehand, thereby reducing the likelihood of confrontation with the authorities at the site of installation.

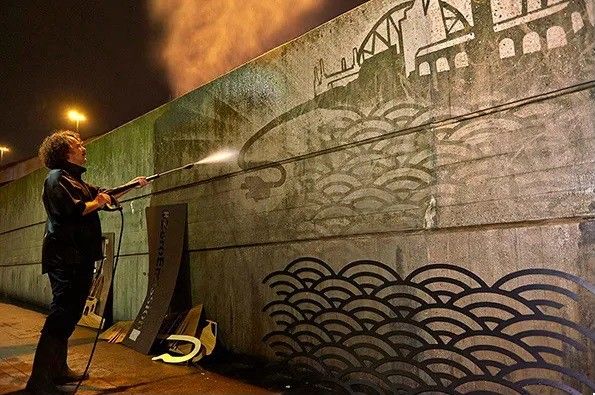

Reverse graffiti

It’s a method of creating images by removing dirt from a surface (also known as clean graffiti, dust tagging, grime writing).

Mosaics

Tile in various shapes, sizes, and colors is widely employed for street art making due to its inherent durability and vibrant visual impact.

Public acceptance

There’s still a debate concerning whether the practice is art or vandalism. There’s still a fine line between appreciating it and taming it.

Historically, most artists have taken to the streets not to showcase themselves but to bring awareness to issues. So, as an opposition to the established order, street art usually shares a strong political or social message and continues to be placed in unauthorized venues. But lately, street artists are increasingly commissioned to create in public places, and these works are generating considerable interest among museums, galleries, and collectors, thus being turned into a commodity and an object of appropriation by the pop culture.

Street art should be distinguished from public art. The former is found in urban public space and considered rebellious and illegal, risking being removed at any time, while the latter is officially sanctioned by cities or property owners and seen as culturally enriching and socially acceptable.

Public attitudes largely depend on individuals’ opinions about acceptable behaviors in public space. Today, more and more people tend to regard street art as a positive thing. Its unique attributes, such as a “celebration of existence” and a “declaration of resistance,” are heavily reliant on its location. Plus, the difference is in the painter’s image — whether it’s the artist, activist, writer, vandal, illustrator. People’s perception is changed by how it is communicated.

So is there “good” street art and “bad”? Everyone has their own answer. In any case, it’s essential to understand that, like any art, it doesn’t have to be aesthetically agreeable. The power is in the emotion. In street art, the most important thing is to engage the observer in a dialogue. It performs a phenomenon that is, through self-transformation, constantly metamorphosing the reality of modern art.

Streets & SketchAR

With the growth of various graphic software and technologies, street artists now have many tools at hand to help create and distribute their works. SketchAR, in particular, allows artists to better prepare for their graffiti pieces, especially large-scale ones. The app overlays a virtual image on a surface to help trace the drawing from a smartphone. Let’s see how it works in practice.

Anastasia Kraseva, Russia

Multidisciplinary artist, art director at MyBuddy.ai, member of Vitae Viazi art crew

In creating my art, I employ different tools: aerosols, brushes, rollers. Materials and surfaces always issue their own corrections, sometimes you need to look for a special solution to make them friends. So it’s important to combine things that seem incongruous at first glance — discoveries are born during experiments.

Some artworks are likely to lose their quality if the sketch is carelessly transferred onto a large surface. The SketchAR app not only gives it accuracy, but also significantly increases the speed of scaling and tracing images.

Anatoly Akue, Russia

Graffiti artist and abstract painter

It’s interesting for me to play around with materials and approaches, dealing a lot with shape and color — that does pave the way for creating new artworks.

In SketchAR, I love the image transfer feature that helps many people take the first step in their art and try to draw what they might find difficult. The app provides the basics.

As a social phenomenon and artistic expression of recent generations, street art has found its way into the core of contemporary art. Today, it’s something more than just a movement — it’s a visual language, with many tongues and accents.