History

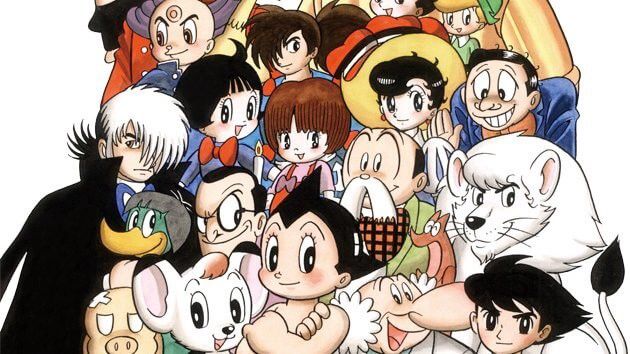

Anime roots go back to the early 20th century when Japanese filmmakers began experimenting with animation techniques invented in the West. At that time, all anime were intended primarily for the Japanese market and, as such, used many cultural references unique to the country. The first notable work was The Tale of the White Serpent, a feature-length, full-color animated movie released in 1958 by Toei Animation. The distinctive style of anime art began to take shape in the 1960s under Osamu Tezuka, the artist behind Astro Boy. He was a leading figure in manga — black-and-white comics that most anime were originally based on. It was Tezuka who created the aesthetic that is still most associated with anime to this day.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Japanese animation started gaining wide international popularity. During that period, cult series such as Dragon Ball, based on Akira Toriyama’s manga, appeared, Saint Seiya also known as The Knights of the Zodiac, Captain Tsubasa, exported as Super Champions, Rurouni Kenshin, known in the West as Samurai X, Sailor Moon, Pokémon, etc. Gradually, anime has evolved into a culture producing diverse pictures, intended not only for children.

Philosophy

“Anime” is a shortened version of the Japanese word “animēshon” (アニメーション), which was adopted to refer to all animated productions for television, film, or video in Japan. But the term became firmly established in the mid-1970s, before that, they were called “manga-eiga” (cartoon movies; “manga” literally means “whimsical pictures” in Japanese). And that’s not the only source of inspiration for anime. Often, anime series are created on the basis of light novels (ranobe), young adult novella-type stories printed in conjunction with illustrations, which also vary in genres — from romance dramas to horrors, mainly with fantasy plots. But, of course, today there are many completely original shows.

Anime is known for its colorful and singular eccentric characters and deep storylines. This is connected with the fact that its Japanese creators are less inclined to experiment with new technologies than animators in other countries, they devote a lot of time to making attractive and interesting character portraits and plotting.

The Japanese Ministry of Education officially recognizes anime as an art form that is among the most important forms of artistic expression in modern Japanese culture.

Most anime display consistent techniques in stylized exaggeration. Body proportions of human characters tend to accurately reflect the proportions of the human body in reality. Although sometimes animators deliberately modify them to get super-deformed characters. A common iconic design feature of many anime humans is abnormally big eyes and expressive or uniquely styled hair. Unrealistic colors in them are often used, for example, to denote personality, etc. Anime is being drawn to look flat, the depth and mass can be added optionally using colors, shadows, and highlights. Inking, which is influenced by Japanese calligraphy and painting, emphasizes clean lines. It’s flatter in appearance because less detail is used on the area of skin and clothes. As anime characters are mostly being made with long slender lines, there is a certain elegance in their creation. In fact, a lot of them look like elves.

Another key point that distinguishes anime from popular Western animation is its emotional content. It tends to focus on action and intrigue regardless of the genre, demanding great involvement from the viewer. Most pictures adopt serious moral philosophies from real-life situations. So things like decision-making, the ability to overcoming losses, and the importance of family relationships form the cornerstone of almost any anime.

Genres

Anime defies simple categorization. Its subject matter ranges from the incredibly cute to realistic depictions of violence. Series creators always clearly define the gender, age, and approximate expectations of their viewers. Let’s go through some of the best-known ones.

KEMONO. It’s mainly intended for children and involves comedy. The originality lies in anthropomorphic animal characters.

KODOMO. The genre has a simple plot with familiar stories, short duration, daring and funny style. It’s aimed at a child audience and differs from others in that it doesn’t contain an element for adult audiences.

ROMAKOME. It’s a comedy with a touch of romance for all types of audiences. The action usually takes place in school life with elements of fantasy and the supernatural.

MEITANTEI. This reveals stories of a detective nature, containing intrigue and mystery.

MECHA. It’s science fiction with a focus on mechanical innovation, featuring large-scale robot battles and/or action sequences.

CYBERPUNK. This is set in a devastated futuristic world. It commonly contains a crucial element of tech advances accompanied by the social order.

SPOKON. It belongs to sports content that emphasizes values such as companionship, physical and mental effort, friendship as well as competition and rivalry.

SHōJO. It’s aimed at girls and women, contains entanglements, comedy, and love conflicts. The characters are usually teenagers. The main thing is the girl and the issues of her personality formation in everyday life.

MAHō SHōJO. In this one, most of the characters possess magical powers to protect something. It usually involves both social and school life, where the main characters are girls or female adolescents.

MAGICAL GIRLFRIEND. The story centers on a female character who may be an alien, angel, demon, god, or robot. She builds a relationship with a human either of love or friendship.

JOSEI. It’s a more realistic female genre that focuses on experiences of college, high school or the life of adult women; mostly doesn’t contain explicit material.

HAREM. Here, the main male character is surrounded by several women. They’re all typically inside a comedic and oftentimes even romantic situation. There is also a reverse harem.

SHōNEN. It’s gendered for boys (men). The theme is a little bit simple but with a lot of action, whether it’s fights or a deeper plot with some romance.

SEINEN. It specifically targets male viewers between the ages of 18–40. The story often includes fairly explicit content such as gore, sex, and violence.

ECCHI. The genre is full of slight sexual scenes (mild enough for the general audience) and scenarios derived from sexual innuendoes. It’s mostly played by male characters, often with a little love experience to add some comedy.

HENTAI. The name literally translates as “pervert”. Unlike ecchi, it focuses on explicit sexual content rather than its storyline and progression.

YAOI. This is a shōjo variation. The theme is still one of the romantic relationships, only in men and in a much more mature light. It’s very popular with female audiences.

YURI. It’s the same as yaoi, the only difference is that the action takes place between women.

GEKIGA. It’s intended for an adult audience, not because it contains sexual material, but because it refers to dramatic images. It commonly has a complex plot and focuses on people’s everyday lives.

GORE. This style is characterized by extremely violent and bloody content. It’s more entertaining when created with elements of intrigue, black comedy, or romance.

Notable creators

Despite the poorly defined drawing distinctions in Japanese animation, there is no free-flowing anime style as such. All of its varieties are strongly attached to their creators.

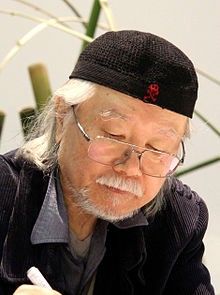

Osamu Tezuka is the one who created the famous drawing style, on the basis of which subsequent artists developed other anime styles. His character visualization features have come to be regarded as canonical: huge detailed eyes, a rounded head, and simplified shapes. By the way, Tezuka borrowed the manner of using big eyes to convey emotions from Walt Disney.

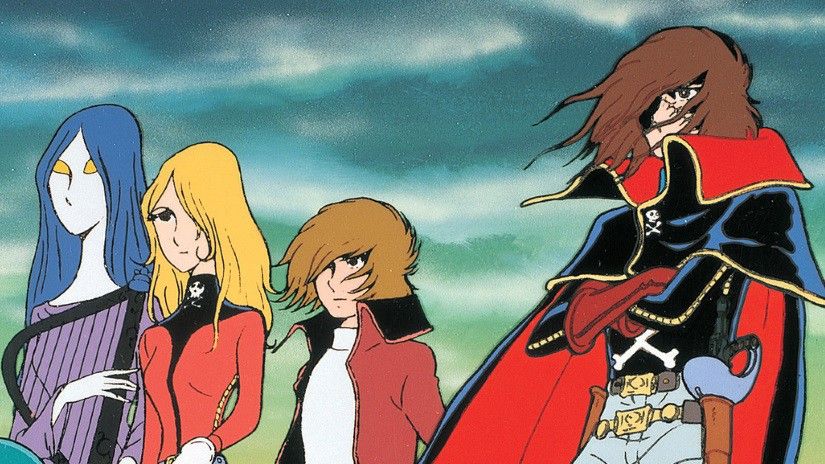

Anime by Tezuka’s contemporary LeijiMatsumoto has always been distinguished by a mysterious and tragic plot, as well as the depiction of female characters. His style stands out even today, thanks to their unusual elongated eyes, slender noses, and very small lips.

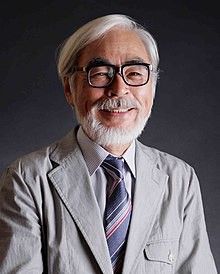

The most famous and award-winning anime director in the world, Hayao Miyazaki is noted not only for his very deep, breathtaking plots but also beautifully drawn backgrounds that give a dreamlike feeling. Miyazaki is great with color and chiaroscuro, his characters are easily recognizable by quite natural eyes, harmoniously located on the face.

Other anime creators currently helping keep the industry fresh include:

• Makoto Shinkai, commonly referred to as the “New Miyazaki” (Your Name, Weathering with You, The Garden of Words, 5 Centimeters per Second);

• Masaaki Yuasa, known for his wild, surreal, freeform style (Devilman Crybaby, The Night is Short, Walk on Girl, Lu over the Wall);

• Mamoru Hosoda, remembered for strong elements of realism and social issues (Digimon: The Movie, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, Summer Wars, Mirai);

• Yuzuru Tachikawa, a new talent, telling thrilling action stories filled with twists and turns (Death Billiards, Death Parade, Mob Psycho 100, Deca-Dence);

• Hiroyasu Ishida, a breakout star, independently producing animated shorts and uploading them directly to the net (Fumiko’s Confession, Rain Town, Fastening Days, Penguin Highway);

• Naoko Yamada, a “method” director, emphasizing the minds of the characters (Tamako Market, K-On!, Liz and the Blue Bird, A Silent Voice).

Anime is a great form of expression of the human imagination. Its diversity of themes, deep handling of the characters, and quality of animation evoke emotions in people. Despite mixed public opinion, we believe that looking at anime and also further back into Japanese artwork as a whole can be a highly informative experience for any artist in any genre. The point is anime has already made its mark on the Western modern art world.